First Video Here

Second Video Here

~ (See article two here, part three here, and a Video of articles one and two here, and video of past 3 here)

By Nick Sayers

ACTS 12:3-4 And because he saw it pleased the Jews, he proceeded further to take Peter also. (Then were the days of unleavened bread.) And when he had apprehended him, he put him in prison, and delivered him to four quaternions of soldiers to keep him; intending after Easter to bring him forth to the people. KJV

So when he had arrested him, he put him in prison, and delivered him to four squads of soldiers to keep him, intending to bring him before the people after Passover. NKJV

English has risen to become the dominant world language. Because most Christianised nations use English as their chief means of communication, for English-speaking believers, it is crucial to understand the history of our language accurately ourselves, before presenting vaguely constructed etymologies, particularly when expounding the words in the Bible. Many cults, which prefer old wives’ tales over the word of God, despise the very word Easter believing it to be a Christianised pagan festival of the spring goddess Ishtar. Many good Christians feel obligated to their conscience to reject celebrating Easter because they too believe it to be based on idolatry and paganism. The traditions which have been added to Easter have not helped either. Most English-speaking people associate chocolate eggs and rabbits with Easter as much as they do the celebration of Christ’s resurrection.

In most languages the word for Easter is exactly the same as the word for Passover, so the relationship between the feast of Passover, and the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, is directly linked. A few examples are; Latin Pascha, French Pâques, Italian Pasqua, and Dutch Pasen. All these words mean both Easter and Passover, only the context formulates the difference. With the exception of English and German, all other European languages do not have separate words for Easter and Passover, but simply use a single term derived from Pesach, the Hebrew word for Passover.

In one way, this is an advantage to the believer, who immediately associates Jesus Christ as the Passover Lamb. Whether reading the New or Old Testaments, the association between Christ and the Passover is clearly seen. This was also the case in the original Greek language which uses the Greek word Pascha for both Passover and the resurrection of Christ. This has been the same for 2000 years in the Greek. Even if you look up a modern Greek dictionary it will tell you that Pascha means both Easter and Passover.[1] This was also the case in English until Tyndale coined the term Passover. But as we shall see, the English rendition of Easter and Passover in the King James Bible is superior and needs to be exalted into its rightful place in English Bible versions, dictionaries and Christian literature again. This does not conclude that the English is superior to the original Greek, which is a form of Ruckmanism,[2] but in this particular instance there is a special feature in the KJV, which is made clear in the original Greek when read in context, but is made abundantly clear by the scholarship of the KJV translators. Just as most Bibles include things like capitalisation of deity or have the words of Christ in red, and other helps, so too did the KJV translators make the Old Testament Passover and New Testament Easter easier for the reader to understand in context.

When the Bible was being translated into the Latin language in the fourth century, when translating the word Pascha, which can mean both Passover and Easter in Latin, Jerome simply used the same Greek word without creating a new Latin word in its place, thus Pascha was basically un-translated.

In the first translation of the entire Bible into English, the hand-written Wycliffe Bible in 1382, appears basically the same un-translated Latin word, Pascha.[3] When we come to the Latin word Pascha it is transliterated without an English equivalent. The words used were Pask and Paske, still a basic type of the Hebrew word Pesach and the Greek Pascha. Later when Roman Catholic scholars translated the Douay-Rheims Bible from the same Latin Vulgate in the 17th century they used the word Pasche, which gave it a more English feel, but was still in essence un-translated. Wycliffe’s version translated Acts 12:4:

And whanne he hadde cauyte Petre, he sente hym in to prisoun; and bitook to foure quaternyouns of knyytis, to kepe hym, and wolde aftir pask bringe hym forth to the puple.

So we can see the English language in the 1300s had the same characteristics as most foreign languages do today, concerning the translation of Pascha as meaning both Easter and Passover. Then Tyndale gave us a greater advantage by using the word Ester (Easter) in his translation and then later inventing the term Passover. Ultimately this gave us two separate words for two distinct occasions. It must be noted that the Anglo Saxon term Easter was used much more frequently in common literature to denote the Passover and the celebration of the resurrection than the Latin Pask ever was. Pask was basically a synonym for Easter (meaning both Passover and Easter) but was mainly used by the clergy.

So as we can see, the word Easter in Anglo Saxon was used for both the Jewish Passover and the celebration of the resurrection, and also was very commonly used.

William Tyndale was a brilliant scholar and was first to incorporate Easter in an English Bible and he also invented the word Passover. William Tyndale translated and printed the New Testament in English and the first five books of the Old Testament between 1525 and 1535 in Germany and the Low Countries while in exile. He was the first person to ever print an English translation. He worked from the original Greek and Hebrew texts at a time when knowledge of those languages in England was rare. He was educated at Oxford University and later at Cambridge where he also lectured and became skilled in not only Hebrew and Greek, but also Latin, Italian, Spanish, and French with such fluency that Herman Buschius, a friend of Erasmus, stated that: “whichever he spoke you would suppose it his native tongue”.[4]

Tyndale was responsible for the insertion of both Easter and Passover in the English Bible. In his 1525 New Testament, Tyndale used the English word Easter to translate the Greek word Pascha. Pascha, being formerly transliterated in Wycliffe’s version, was for the first time in a Bible translation, translated into a unique English word.[5]

As we can conclude from the Anglo Saxon terms mentioned above, English people celebrated the season around the Jewish Passover as Easter. Also it must be pointed out that Tyndale used Easter as a synonym expressing the Jewish Passover and never in association with a pagan festival. Some modern day scholars conclude that the word Easter has pagan origins, but the facts are that the word Easter and also the celebration of Easter are entirely Christian. Easter was not only a synonym for Passover, but also a descriptive word revealing the New Testament fulfilment of the Passover, in Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection. The Greek word Pascha occurs twenty-nine times in the New Testament, and Tyndale has Ester (or Easter) fourteen times, Esterlambe eleven times, Esterfest once, and Paschall Lambe three times. In 1525, Tyndale’s New Testament was printed. Five years later in 1530 he printed the Pentateuch—first five books of the Old Testament. When Tyndale was working on the New Testament, the word Ester (Easter) was adequate to translate Pascha, but when he started the Old Testament book of Exodus, in 12:11 he discovered the word Easter, which means resurrection, was inappropriate. This problem involved the translating of the Hebrew word Pecach, which if translated Easter, meaning resurrection, would form an anachronism (from the Greek ana, “against,” and chronos, “time”), which is something located at a time when it could not have existed or occurred. Basically, if he used the English word Easter, which describes Christ’s formed the word Passover, and used it in all twenty-two places of the Old Testament Pentateuch. The word Passover comes from the idea that God passed over the houses of the Israelites, who had marked their doorposts with blood in obedience to God, and the children of Israel were spared when God smote the firstborn sons of the Egyptian taskmasters on the eve of the Exodus. The sons of Israel were thus redeemed from the land of sin, Egypt, and redeemed from Pharaoh to serve Jehovah. The Hebrew word Pecach was understood by the Israelites at the time to mean skip over or to limp. So Tyndale used two words “pass” and “over” meaning to skip over or limp over, which shortly became the one word Passover in the 1530 Pentateuch, but Ester (Easter) remained in Tyndale’s revision of the New Testament in 1534. Brilliantly, Tyndale’s Passover also incorporates the pass sound as in Pask and Pascha. Interestingly, the word Passion which means suffering, seems to have evolved from Pascha. Perhaps Gibson should have called his film The Pascha of the Christ!

Since the time of the King James Version until the early twentieth century, the term Easter was commonly identified by believers solely as the celebration of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Before Tyndale, Easter was the chief word used for the Jewish Passover by Christians. This is because Easter and Passover are the same season, Jews celebrating the shadow, and Christians celebrating the fulfillment. The word Easter has illustrated to the Englishman much more than simply the Passover celebration, but through Tyndale’s addition of Easter, construction of the word Passover, and later with the King James’ translators correctly re-applying Easter only once in Acts 12:4, it gives significant insight into revealing the fulfillment of the Passover in Christ. It exalts Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection above all. In past times Easter to the English speaker not only saw Christ as the Passover lamb but clearly defined the difference in the celebrations, one containing the promise and one fulfilling the promise. Modern criticism has blurred that revelation.

After 1611, the Old Testament Easter, which formerly meant both Passover and Easter, became solely the old covenant Passover, a trend Tyndale had begun to accomplish. Because Luther’s version was printed before Tyndale’s, Tyndale would have had the advantage of being able to cross reference and improve any inconsistencies.

The English Easter and German Oster go hand in hand. Many English scholars refered to German as "the mother tongue."

Luther’s translation was a strong influence on Tyndale’s New Testament. Because of persecution in Catholic England, Tyndale left England for Germany. It is strongly believed that he met with Luther in Germany in 1525, as many of Tyndale’s beliefs were, in essence, Lutheran. By the end of the year, Tyndale had printed the New Testament in English. It is likely that Tyndale’s use of Easter in his New Testament is also indebted to his knowledge of Luther’s German translation, which uses Oster (pronounced 0uster) in the same way as Tyndale uses Easter. Because the English Anglo Saxon language originally derived from the Germanic when the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes came to England in the 5th and 6th centuries, there are many similarities between German and English. Many English writers have referred to the German language as the Mother Tongue! The English word Easter is of German/Saxon origin and not Babylonian as Alexander Hislop falsely claimed, and as we shall see later. The German equivalent is Oster.[6] Oster (Ostern being the modern day correspondent) is related to Ost which means the rising of the sun, or simply in English, east. Oster comes from the old Teutonic form of auferstehen/auferstehung, which means resurrection[7], which in the older Teutonic form comes from two words, ester meaning first, and stehen meaning to stand.[8] These two words combine to form erstehen which is an old German form of auferstehen, the modern day German word for resurrection[9]. The English Easter and German Oster go hand in hand.

Tyndale with his expertise in the German language knew of the Easter - Oster association. Luther obviously defined Oster both as a synonym for the Jewish Passover and a phrase used for the resurrection of Christ. In Luther’s German New Testament we find Ostern, Osterlamm, Osterfest, Fest, and only once das Passa (Hebrews 11:28). In His Old Testament he used the German word Passaopffer (an obvious forerunner for Tyndale’s Passover), Osterfest, Ostern, and Osterlamm once each. In Exodus 12:11 Luther rendered Passah with a marginal note referring to the Osterlamm. Even in contemporary German the phrase das jüdische Osterfest (the Jewish Passover) demonstrates that the German Oster can mean both the Jewish and Christian festivals. In fact the meaning of the German word Ostern is today just as the English word Easter was until the KJV translators skilfully put it in its correct semantic range in Acts 12:4, thus separating forever the Old Easter and the New Easter as we shall see.

Before the 1530s, England always used the word Easter for both the Jewish Passover and the Resurrection celebration. Sometimes clergy used the Latin Pask or Paske, but predominantly Easter. Here are two non-biblical examples of Easter and Passover being synonyms. In the Peterborough Chronicle of 1122 we read:

A 1563 homilist spoke of “Easter, a great, and solemne feast among the Jewes”. Today, Pascha vaguely remains an adjective meaning Easter, as in Paschal candle. In Scotland and the North of England, children hunt for Pasch eggs.

In the 1537 Matthew’s Bible which incorporated Tyndale’s work on the Pentateuch, the word used was Passeover, but there were references to Ester in the chapter summaries in Leviticus 23, Numbers 9 and Deuteronomy 16.

In the 1539 Great Bible they used Passeover 14 times, while Ester appears 15 times all in the New Testament. The Great Bible translates Acts 12:4 this way:

In the 1557 version of the Geneva Bible, every place had Passeover except Acts 12:4, where it had Easter, which was identical to how the King James Version translated it.

In the 1560 version of the Geneva Bible, which became the most popular of the Geneva Bibles, the word Easter was completely substituted with Passeouer on all occasions. The Geneva Bible of 1560 does not use Easter anywhere. Acts 12:4 reads:

In the 1568 Bishops’ Bible, Easter appears twice, in John 11:55 and Acts 12:4. The Bishops’ Bible of 1568 translates Acts 12:4:

In the 1611 Authorised Version, Easter appears once in Acts 12:4.

Until 1611, English-speaking people had always associated the word Easter with the celebration of Passover and the prophetic implications which occurred at Christ’s death and resurrection. They saw that the Old Testament shadow was the Passover and that the New Testament fulfilment was Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection called Easter.

The King James Bible finalised 86 years of change in the use of Easter and Passover. After seeing what Tyndale had begun and the refining of the word Easter within almost a century of various translation attempts, the KJV translators caused the semantic range of Easter to be translated only once as Easter in Acts 12:4. This was because in every instance in the New Testament except Acts 12:4, the Greek word Pascha represented the pre-resurrection Passover, i.e. the Jewish celebration. In other words Christ had not yet died as the Passover lamb for the whole world. But in Acts 12:4 it is a post-resurrection Passover, where Christ had died and was risen.

The Greek word Pascha appears 29 times in the Greek New Testament. In 28 of those instances it is referring to the Old Testament Passover. But in Acts 12:4 it is referring to the New Testament celebration which was the Lord’s Supper. Christ had become the Lamb of God and replaced the old Passover sacrifice with the new covenant in His blood. Therefore the old Passover type was replaced with the celebration of the death and resurrection of Christ which is the fulfilment called Easter, meaning resurrection.

Because the KJV translators rendered this word once, in Acts 12:4, with the understanding that it was the Christian resurrection celebration being celebrated and not just the old Passover, it stands to be the most accurate of all the English translations concerning this topic. After 1611, with the predominance of the KJV and with the process of time, Passover became known as an Old Testament word, and Easter became known as a New Testament word. The only other time Pascha is mentioned in the post-resurrection semantic range is in 1 Corinthians 5:7, “For even Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us”. Tyndale’s Bible has, “For Christ our Easter lamb is offered up for us”. Obviously, with the semantic range of the Old Testament Passover, and the New Testament Easter, this scripture is correctly translated Passover by the KJV translators, as it alludes to the Jewish custom of carefully putting away from their houses all leaven upon the approach of the feast of the Passover, thus making the word Passover more appropriate than Easter or Easter lamb in the context. A paraphrase would be “For Christ our fulfilment of the Old Testament Pascha is sacrificed for us”. Tyndale was correct to translate Easter lamb and not Passover because the terms were not clearly defined until 1611.

With this in mind, let’s look at what Hislop claimed about the KJV in his The Two Babylons:

Linguists and true Assyriologists would laugh at the claims made by Hislop’s pseudo-scholarship. Since it does not hold up under basic scrutiny, its claims about Easter must be abandoned. Firstly, while Hislop boldly claimed Easter was pagan, he offered no real proof. Alexander Hislop also stated:

It must be noted that most cults such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Seventh Day Adventists gravitate warmly to Hislop’s false ideas. While he does offer some sound information about pagan traditions becoming Roman Catholic practice in his book, he fails to recognise that biblical Christian traditions that were formed from the Word of God were initiated by Jehovah God Himself and have no roots in paganism whatever. Hislop fails to see that the Passover, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, First Fruits, etc, were ordained by God who did not borrow ideas from Israel’s pagan neighbours.

Hislop’s whole theory is based merely on phonetics and not on historical verification. His whole argument is based on the false notion that Easter sounds like Ishtar and he therefore concludes that they must be related. Any linguist knows that this type of conclusion is unreasonable. Then without a single shred of evidence Hislop denounces the biblical Christian celebration of “Easter” as pagan because of this phonetic similarity.

Hislop claims that the word Easter is of British origin, he then goes on to theorize that the word somehow became tied to the Hebrew word Ashtoreth which then somehow became attached to the Greek Astarte and which is the same as the Babylonian Ishtar. Hislop performed all these linguistic gymnastics without any understanding at all of the Germanic roots of Easter. While Hislop has absolutely no evidence to support his theory, there is a library of evidence against his theory.

Hislop fails to recognize the relationship between the word Easter and the German Oster. As mentioned earlier Easter is cousin to Oster. The German word derives from erstehung (resurrection), which itself derives from ost (east) and erst (first) in combination. The fact that this essential piece of information is not mentioned even once in Hislop’s book proves without a shadow of a doubt that he did not understand the basic etymology of Easter.

Furthermore Easter was not originally pronounced and spelled Easter but Ester which is more directly from the German ost and erstehung. When Tyndale, who was fluent in German, employed the word in his New Testament he used Ester, not Easter. Eventually throughout the reformation period of the 1500’s the English word Ester morphed into Easter. This demonstration of the Ester/Oster bond again reinforces the Saxon and Germanic etymology, in preference to some ancient Babylonian goddess. This is plain for all to see and elementary to skilled linguists.

But the unequivocal traces of that worship are found in regions of the British islands where the Phoenicians never penetrated, and it has everywhere left indelible marks of the strong hold which it must have had on the early British mind.[12]

This statement demonstrates that Hislop was surprised that the word Easter is used so frequently in England, concluding that the influence of the Phoenicians must have been much greater than previously thought, thus demonstrating again that he knew nothing of the link to the German Oster which all evidence leads to. C.F. Cruse in 1850 AD pointed out three years before Hislop wrote The Two Babylons, that Our word Easter is of Saxon origin and of precisely the same import with its German cognate ostern. The latter is derived from the old Teutonic form of auferstehen / auferstehung, that is—resurrection.[13]

The etymology of Easter is easily traced to the German word for resurrection, not to some fabricated pagan goddess, for which there is not a crumb of evidence. A child could understand how Easter came from Oster, but skilled linguists grapple to decipher Hislop’s confusion, because like evolution, it is an inexhaustible myth, i.e. a wild goose chase! You can spend forever going through names of Istar in Latin, Hebrew, Greek, etc, and you will be none the wiser.

According to scripture, Jehovah initiated both Passover and Easter. The Hebrews didn’t need the intermediary of pagans. Moses states in the book of Exodus that God gave the Passover Feast to the Jews, and that God gave the specific date upon which the Passover was to be celebrated, the 14th of Nissan (formerly called Abib, before the Exodus). The Jews did not borrow the Passover feast or the Passover date from anyone, but got both the feast and the date of the feast directly from Jehovah God. The Easter celebration, which is the Christian fulfilment of the Jewish Passover, occurred on the very same date as the Jewish celebration, the 14th of Nissan. Christians did not need to copy the Resurrection idea or the Resurrection date from pagans. Christians celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ because Jesus Christ literally rose from the dead in fulfilment of the Passover on that day. Hislop speculates that the Christian celebration was not based upon the Jewish Passover, but that Christians somehow abandoned the fulfilment of the Jewish Passover and instead celebrated an unknown fertility festival. There is no evidence for this apart from what Hislop theorised. If you’re a Bible believer, you believe the Bible—if you’re superstitious, you believe Hislop.

Ralph Woodrow who repented of writing many Hislop-style books pointed out that Hislop theorised that Nimrod, Adonis, Apollo, Attes, Ball-zebub, Bacchus, Cupid, Dagon, Hercules, Januis, Linus, Lucifer, Mars, Merodach, Thithra, Molock, Narcissus, Oannes, Oden, Orion, Osiris, Pluto, Saturn, Teitan, Typhon, Vulcan, Wodan, and Zoraster were all one and the same god! By mixing myths, Hislop supposed that Semiramis was the wife of Nimrod and was the same as Aphrodite, Artemis, Astarte, Aurora, Bellona, Ceres, Diana, Easter, Irene, Iris, Juno, Mylitta, Proserpine, Rhea, Venus, and Vesta. With these types of generalisations one must seriously consider whether Hislop’s book has any redeeming qualities at all.[14]

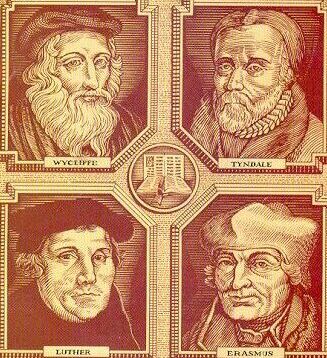

In stark contrast, let’s take a quick look at the scholarship of some of the King James Version translators.

Lancelot Andrews,[15] one of the chief translators of the Authorised Version, spoke 15 European languages which were, at the time, the majority of the modern languages of Europe. He had private devotions all written in Greek. He is still regarded as one of the greatest scholars ever! Lancelot Andrews was fluent in 15 languages. Considered a genius, he was just one of 57 brilliant scholars who helped translate the Bible.

William Bedwell[16] was an eminent Oriental scholar whose fame for Arabic learning was so great that scholars sought him out for assistance. He was the first person who considerably promoted and revived the study of the Arabic language and literature in Europe. In 1612, he published in quarto an edition of the Epistles of St John in Arabic with a Latin version. He compiled an Arabic lexicon (dictionary) in three volumes, and also began a Persian dictionary. He was educated in cognate languages and thoroughly conversant in the science of Semitic linguistics, i.e. he knew a great deal about Hebrew’s sister languages and Arabic, Persian, Syriac, Aramaic, Coptic, etc.

Miles Smith[17] deeply studied the 100 church fathers from 100 to 300 AD and 200 more who wrote from 300 to 600 AD in Greek and Latin and made his own comments on each of them. He was well acquainted with the marginal comments in the Hebrew language. He was fluent in Hebrew also an expert in Chaldee, Syriac, and Arabic, so that they were almost as familiar as his native tongue.

Henry Savile[18] was famous for his Greek and mathematical learning at a young age. He was Queen Elizabeth’s tutor in Greek and Mathematics. He translated countless ancient works from Latin and Greek his chief work being the first to edit the complete work of Chrysostom, the most famous of the Greek church fathers, in eight large folios. A folio was the size of a large dictionary or encyclopaedia.

John Bois[19] had read the entire Bible by the age of five in Hebrew! By the age of six he wrote Hebrew in a reasonable and stylish character. He was also just as skilled in Greek by his mid teens. He was known to study continually from 4am to 8pm—i.e. 16 hours straight. He had a library which contained one of the most complete and costly collections of Greek literature that had ever been collated. He left over 30,000 pages of writing when he died. He could read the Greek New Testament like he read English.

This is a small portion of the testimonies of the 57 translators who translated the KJV. How sad that in this day and age we trust someone like Hislop who was uneducated in the basics of linguistics and barely knew any English etymology at all let alone any ancient Semitic languages fluently.

Many Bible critics and translators today who perhaps know how to use a Strong’s or Vine’s, or took a year or two of Greek or Hebrew at a Bible school, have followed in Hislop’s footsteps. What a shame that believers devote so much time arguing against Easter, something that Christ himself instituted, or waste so much time attacking the KJV Bible.

It also seems strange if not blasphemous that we as Bible-believing Christians could think that the King James Version translators would insert the name of a pagan deity in place of the word Pascha. Imagine if we placed Krishna or Allah in its stead.

To think that the world’s most famous translation could get it so wrong here is sheer ignorance on our behalf. To believe that Tyndale, Cranmer, Martin Luther, Coverdale, Matthews, the translators of the Great Bible, and the Bishops’ Bible, the King James Bible, were referring to a pagan god of the spring called Ishtar is so absurd that it becomes humorous when examined.

If this hearsay is true, then Luther and Tyndale who named Christ the “Easter-lamb” were being blasphemous, as it would be like calling Christ the “fertility goddess lamb!” Imagine calling Christ the “Allah-lamb”, or the “Buddha-lamb”. But I suppose that is why people have rejected Easter, for conscience sake. But with the information provided, it is time for Christians to examine Easter in a logical way and not follow conspiracy theories, which is usually the practice of cults. Modern biblical criticism, more than anything else, has weakened and almost destroyed the high view of the Bible previously held throughout Christendom.

And with great power gave the apostles witness of the resurrection of the Lord Jesus: and great grace was upon them all. Acts 4:33

The modern KJV 21st century version and the Third Millennium Bible both read Easter in Acts 12:4, while every other modern translation has Passover. While it was correct to translate Pascha as Passover in the 16th century, it is not factual to state that Easter is an erroneous translation of Pascha today. I believe that the word Easter should be resurrected (no pun intended) from its current state in modern translations, dictionaries, and in our personal worship. The celebration of Easter should be a time of jubilation, not a time to talk about myths, fables and old wives’ tales. Just as the Jews remembered the Passover, so too should Christians remember Christ at communion. So next time you break the bread and drink the wine at Easter, consider the Passover lamb, and the celebration of Easter, which has been a part of Christianity since the resurrection of Christ.

The early church never debated whether or not to celebrate Easter, but only debated the day to celebrate it on. The King James translators concluded that the insertion of the words in Acts 12:3 “Then were the days of unleavened bread” just before the inclusion of the word Easter was enough evidence to prove that Luke was talking about the Christian Pascha i.e. Easter, the celebration of the resurrection.[20]

Links for futher study:

End of article